There is an ongoing battle for cultural hegemony in France. Far-right ideologies are being normalized, their stigmatizing vocabulary thus not only gains public acceptance but also comes to shape the government’s agenda on minority rights. Two derogatory terms have gained salience during the last year: islamo-gauchisme and wokisme. They fuse together existing and new scenarios of putative threats to the Republic. Muslims, critical academics and those who speak up against Islamophobia are targets of the new government rhetoric.

One year after the brutal assassination of schoolteacher Samuel Paty by an Islamist terrorist, the French minister of national education launched a new Republican think tank labelled “laboratoire républicain” on October 13th. Jean-Michel Blanquer declared last month that his republican laboratory is designed to “win the battle of ideas” and “defend humanism and universalism” against “wokism”.

Wokism, the new obsession of the French public discourse, was described by Blanquer during the pandemic as a fast-spreading virus. His laboratory, to stay with the metaphor, is now supposed to develop the “cure” for this virus. The ingredients to be used are good old-fashioned republican values, of course. But what exactly does the patient suffer from?

In his address delivered in Paris, Blanquer identified four areas in which wokism creeps in: first and foremost, it befalls the academic field. According to the minister, it suffers due to the spread of a cancel culture, where “real power strategies have been put in place”. Moreover, the media, the cultural world and politics are equally affected by wokism.

A year ago, Blanquer stated, the universities were ravaged by islamo-leftism, an ideology which in his words, made critical academics accomplices of terrorism. In his Interview with radio Europe1, he denounced “ideas that often come from outside, from a model of society which is not ours. We have a Republican, universalist model. (…) I will be very firm against all those who, today, believing themselves to be progressive, in reality make the bed for a form of tolerance to radicalism. This is unacceptable and it leads to the worst.”

While it was then unclear which ideas he meant, one year later, the French discourse has produced a label for such ideologies: le wokisme. This derogatory term includes postcolonial studies, intersectionality, critical race theory (among others) and opposes them to the French Republican model of universalist values. This right-wing catch-all-phrase is used to delegitimize claims for equal representation, positive discrimination or the responsibilities arising from France’s colonial past.

The goal is, clearly, to present these schools of thought as incompatible with French values. They are said to stem from abroad, namely the U.S, and to carry in them a divisive quality. Besides they are presented as corrosive to national unity as well as abetting Islamism, as President Macron maintained is his speech on separatism in February 2020 (see also Norimitsu Onishi’s piece in the New York Times).

The government’s verbal attacks against critical research did not miss their target. Only days after Blanquer’s statement, the resulting polarization within academia was clearly visible, among other places in le Monde. In an open letter supporting the minister, 100 researchers and intellectuals deplored an ideological decay imported from the US, a growing “hatred against whites and France” and a “violent militancy” against “those who still dare to defy the anti-Western doxa and the multiculturalist preaching.” The opposing side emphasized the historically oblivious character of such a view and pointed to the Islamophobia of the state, which places religious minorities under general suspicion in the name of secularism.

This collusion between critical intellectuals and Islamism is very much in line with what Aurelien Mondon calls the French “secular hypocrisy”: “the hegemonic rise of an exclusivist understanding of the concepts of the Republic and, more particularly of one of its cornerstones, one with purposefully fuzzy and multiple meanings: secularism or laïcité” (Mondon 2015: 407).

Ramazan Kilinç shows in a historical account of the Muslim immigration and secularism in France, how the increase in immigrant Muslims in the 1960s led to the state reshaping its general policies toward religious minorities. “This was especially the case after 2001, when European publics became concerned about the so-called ‘Islamist threat.’ French lawmakers and policymakers revised the laws and regulations about the representation of Muslims in civil society and toward the state, the construction of mosques, support for Muslim schools, and the manifestation of Muslim religious symbols in the public sphere” (Kilinç 2019, 62). While laïcité, according to the original 1905 act is supposed to protect the rights of religious groups, in today’s France it is used as a justification for all kinds of constraints and crack downs on Muslim groups, NGOs, charities or Mosques.

As law scholar Rim-Sarah Alouane puts it, Republican values – especially laïcité – are an “argument used to justify repressive, discriminatory, and identitarian policies, in particular toward Muslims.” With the postulation of Islamo-leftist and woke ideologies as a threat to the majority, those who oppose this weaponization of secularism can easily be disqualified as enemies of the Republic.

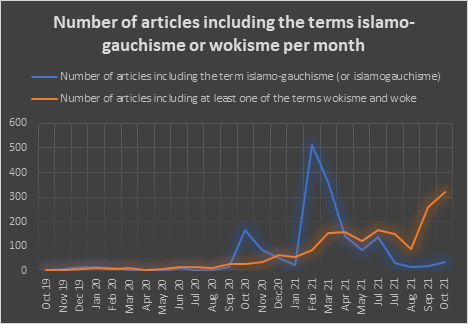

In fact, frequency data suggest that wokisme has taken the place of islamo-gauchisme as the new buzzword. Both link critical research to an assumed interest of outside enemies to undermine French democracy and national unity. The use of islamo-gauchisme peaked in October 2020 and February 2021, right after the two ministers responsible for education and research linked it to an assumed danger from within academia. Wokisme was established at the same time, but used more and more frequently after the immediate shock of the 2020 terror series had worn off. Wokisme seems to be made for quieter times. Nevertheless, both terms do the work of lumping together critics, activists, scholars and Muslims into a vague group of enemies of the majority.

The database includes 104 French media outlets and press agencies accessed via the database Factiva on 22 November 202

Arguably, this political development and its acceptance by the majority goes hand in hand with the extreme right’s struggle for cultural hegemony. This battle of ideas shapes the media discourse, polarizes the public and normalizes conspiracy myths. As a representative survey from October 20th 2021 shows, 61% of the population agree with the statement that a “big replacement” is underway in France. This conspiracy myth, first described by French alt-right pioneer Renaud Camus, maintains that the white, Christian population in Europe is being outnumbered by Sub-Saharan and Muslim immigrants in a concerted attack supported by a global elite. The “big replacement” is one key ideological frame of the Nouvelle Droite. It suggests not only the neo-racist view of incompatibility of different cultures but also the antisemitic myth of a powerful global elite pulling the strings in the background and the threat of a violent replacement of white population in the West.

In France, these conspiracy theories and panics about white extinction fall on fruitful ground. Decades of failed integration politics, concentration of Maghrebi population in the banlieues and consolidated, often racialized, social inequality have prepared a fertile soil for these pernicious ideas. As Charles Taylor puts it “This is a problem not just for integration, but for democracy as such. When you get growing inequalities, people at the lower end check out of democracy and become recruitable for parties offering this utterly simplistic solution”. In combination with the mainstreaming of extreme right ideologies such ideas have made neo-racist stances widely accepted and make the electoral success of Le Pen’s National Rally more and more likely.

References

Kılınç, Ramazan. 2019. Secularism and Muslims in France. In Ramazan Kılınç (ed.), Alien Citizens, vol. 33, 61–84. Cambridge University Press.

Mondon, Aurelien.2015. The French secular hypocrisy: the extreme right, the Republic and the battle for hegemony. In: Patterns of Prejudice 49 (4), S. 392–413. DOI: 10.1080/0031322X.2015.1069063