On October 2, Brazilians went to the ballots to vote for president, state governors, senators, as well as federal and state representatives. In the presidential race, the center-left-wing former president Lula da Silva from the Workers Party (PT) received 48% of the votes, whereas the incumbent far-right-wing president Jair Bolsonaro from the Liberal Party (PL) obtained 43%. According to opinion polls on the eve of the election, around 50% of voters declared they would vote for Lula and around 35% for Bolsonaro.

Apart from the narrower margin of difference between Lula and Bolsonaro, the fact that candidates for governors, senators and representatives supported by and supporting Bolsonaro performed well above what the polls predicted has surprised actors from politics, academia and the media. In São Paulo, Bolsonaro’s candidate for governor, who occupied the second place in the polls, received 42% of the votes, while the PT candidate (whom polls predicted would take first) achieved 37%. In the states of Rio de Janeiro and Minas Gerais, Bolsonaro supporters respectively achieved 59% and 56% of the votes for governor – which means they have already been elected as the Brazilian electoral system only demands a second round when candidates for executive offices receive less than 50% of the votes.

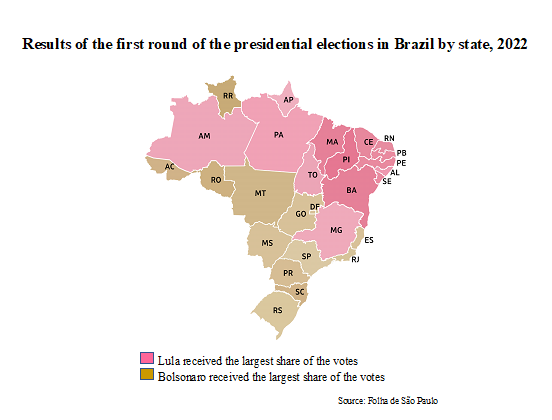

For the second round of the presidential elections, Bolsonaro is counting on the support of his triumphant candidates for governor in these three states, which are the three most populous and wealthiest in the country. In the states of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, Bolsonaro in fact emerged from the first round with more votes than Lula. Lula, in turn, gathered support from the presidential candidates who ended up in the third and fourth places: Simone Tebet from the Brazilian Democratic Movement (MDB) and Ciro Gomes from the Democratic Labor Party (PDT). The electoral map of Brazil shows that Bolsonaro won more votes than Lula in the richer southern, southeastern and central states of the country. On the other hand, Lula had an advantage in the Northeast and North of Brazil. For example, in the city I live and teach, Salvador, capital of the northeastern state of Bahia, Lula obtained 67% of the votes and Bolsonaro only 24%. This geographical distribution of votes between, so to say, the left and right is, per se, not a novelty in Brazil – it has been consistent since the early 21th century.

What is, however, novel is the tectonic replacement of neoliberal forces – which, since the early 1990s following the re-democratization and the enactment of the new constitution, have occupied the niche of the right – by the forces of Bolsonaro and the political constellation around him that has been called Bolsonarism. Those neoliberal forces were internally heterogeneous but gravitated around the Party of Brazilian Social-Democracy (PSDB), founded in the late 1980s by former opponents of the military dictatorship. PSDB ruled the country from 1995 to 2002, with PT as the most important contender in the 1994 and 1998 elections, while the latter won the elections between 2002 and 2014 with PSDB as their main contender. Since the 2018 elections, however, Bolsonaro was able to present himself as the political hegemon within the field of the right and to galvanize this leadership position.

Bolsonaro’s propaganda is based on an engineered fear of the triumph of ‘evil’.

The broader regional divide presented above goes hand in hand with other divides such as income and religion. Like PSDB candidacies before, Bolsonaro has more support than Lula among the middle and upper classes nationwide. Additionally, Bolsonaro draws support from most Brazilian evangelical Christians – a religious segment spread across different churches that has consistently been growing over the past four decades in the country. Unlike the first group, the latter is mainly composed of people with lower incomes.

Through the hands of pastors aligned with Bolsonaro, evangelical churches have worked as conveyor belts for Bolsonarism among the poorer, even though this income group predominately votes for Lula.

Bolsonaro’s propaganda based on an affect of fear particularly resonates within these groups. This sentiment is, first and foremost, an engineered fear of the triumph of ‘evil’. Unlike in Europe or in the United States, the issue of immigration, which is often used for right-wing propaganda, is virtually inexistent in Brazil, meaning that threats to the integrity of the nation are above all considered to be internal. This ‘evil’ is represented by the umbrella concept of ‘communism’ propagated by Bolsonarism. This construct rests on and nurtures a moral panic according to which the heterosexual family is in danger of dissolution by a so-called ‘gender ideology’ that seeks to turn young kids gay while Christianity is under assault by ‘devilish’ practices such as atheism or Afro-Brazilian creeds. ‘Communists’ also attempt to engender unnecessary divisions within the nation by addressing the Brazilian colonial past of slavery, contemporary racism and the legacy of the military dictatorship of 1964–1985.

Brazilian elites have opened a Pandora’s box.

Moreover, ‘communist’ defense of social and economic inclusion and protection threatens meritocracy, that is, the survival and advancement of the smartest and most hard-working people. The middle classes, in particular, have come to resent the empowerment of the poor during the PT terms from 2003 to 2016: economically in terms of access to goods and services as well as symbolically due to the large expansion of higher education opportunities. The underlying meaning of the anti-PT motto ‘I want my country back’ is that this access to goods, services and higher education should remain a privilege of a white elite – a claim that is a striking example of what Aníbal Quijano calls the ‘coloniality of power’. Entrenched in a discourse produced by a coalition of media, partisan agents of the judiciary and the opposition in Congress that equated PT with corruption, the Brazilian middle and upper classes took to the streets in 2015 and 2016 to demand the impeachment of Workers Party president Dilma Rousseff, which came to fruition in August 2016. As other scholars and activists in Brazil, I designate this event as a parliamentary coup: the twisting of legal procedures to serve illegitimate ends. The charges against Rousseff did not evince any crimes, yet the president was nonetheless removed from office.

By undermining democratic institutions in this manner, Brazilian elites have opened a Pandora’s box and the country has subsequently had to deal with the beasts that emerged therefrom. In line with the international trends, politics within the Brazilian right-wing spectrum has turned into anti-politics under the leadership of an authoritarian figure. This has brought lies, conspiracy theories and emotions to the fore. In 2018, Bolsonaro embodied the anti-PT candidacy in a political atmosphere adverse to the Workers Party. In 2022, in contrast, after almost four years of striking incompetence, disastrous mishandling of the COVID pandemic leading to over 680,000 deaths, brutish statements including high doses of misogyny, and widespread impoverishment of the middle and lower classes, it seemed that his authoritarian affront to democracy would be more easily countered. Polls have apparently been unable to grasp the ulterior moves of Bolsonarism, i.e. to capture the undeclared, silent voting tendencies of those who have learned in the past few years that ‘anything is better than having PT back to power’. After almost four years in power and upon having re-structured the field of the right in Brazil, Bolsonarism has, to some extent, become politically normalized and socially more ingrained. The Brazilian right has finally found a mass leader, one very different from PSDB’s elitist intellectuals and technocrats. These are some lessons that we can learn following the first round of the elections in Brazil. If Bolsonaro is elected for a second term, he will be able to follow the steps of Viktor Orbán in Hungary and Recep T. Erdoğan in Turkey by changing legal rules and rolling back democracy – a process in line with what the Bremen Research Group has called “soft authoritarianism” – especially as he would have a large majority in both houses of the congress. The second round will take place on October 30 and, in between, democratic forces should make every effort to identify and learn from failing to counter these new dynamics among the population.